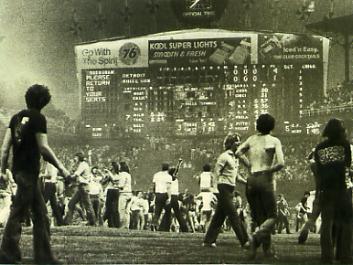

This is my Dad in the middle!!!!

This is my Dad in the middle!!!!

The turnout for this promotion far exceeded all expectations. White Sox management was hoping for a crowd of 12,000, about double the average for a Thursday night game that year. But an estimated 90,000 turned up at the 52,000-seat stadium. Thousands of people climbed walls and fences attempting to enter Comiskey Park, while others were denied admission. Off-ramps to the stadium from the Dan Ryan Expressway were closed when the stadium was filled to capacity and beyond.[6]

White Sox TV announcers Harry Caray and Jimmy Piersall, who were broadcasting the game for WSNS-TV, commented freely on the "strange people" wandering aimlessly in the stands. Mike Veeck recalled that the pregame air was heavy with the scent of marijuana.[7] When the crate on the field was filled with records, staff stopped collecting them from spectators, who soon realized that long-playing (LP) records were shaped like frisbees. Some began to throw their records from the stands during the game, often striking other fans. The fans also threw beer and even firecrackers from the stands.

After the first game (which Detroit won 4-1), Dahl, dressed in army fatigues and helmet, along with Lorelei Shark, WLUP's first "Rock Girl",[8] and bodyguards, emerged and proceeded to center field. The large box containing the collected records was rigged with explosives. Dahl led the crowd in chants of "disco sucks" and a countdown prior to triggering the explosives. When detonated, the explosives tore a hole in the outfield grass surface and a small fire began burning. Dahl, Shark, and the bodyguards hopped into a jeep which circled the warning track before leaving the field through the right-centerfield exit. Thousands of fans immediately rushed the field. Some lit more fires and started small-scale riots. The batting cage was pulled down and wrecked,[9] and the bases were stolen, along with chunks of the field itself. The crowd, once on the field, mostly wandered around aimlessly,[10] though a number of participants burned banners, sat on the grass or ran from security and police.

Veeck and Caray used the public address system to implore the fans to leave the field immediately, but to no avail. The scoreboard simply flashed, "PLEASE RETURN TO YOUR SEATS." Eventually, the field was cleared by the Chicago Police in riot gear. Six people reported minor injuries and thirty-nine were arrested for disorderly conduct.[6] The field was so badly torn up that the umpires decided the second game couldn't be played, though Tigers manager Sparky Anderson let it be known that his players would not take the field in any case due to safety concerns. The next day, American League president Lee MacPhail forfeited the second game to the Tigers, on the grounds that the White Sox had failed to provide acceptable playing conditions. The remaining games in the series were played, but for the rest of the season fielders and managers complained about the poor condition of the field.

For White Sox outfielder Rusty Torres, Disco Demolition Night was actually the third time in his career he had personally seen a forfeit-inducing riot. He had played for the New York Yankees at the last Senators game in Washington in 1971 and the Cleveland Indians at the infamous Ten Cent Beer Night in Cleveland in 1974. The event was deemed newsworthy worldwide.[3]

According to the 1986 book Rock of Ages: The Rolling Stone history of Rock and Roll, "the following year disco had peaked as a commercial blockbuster".[2] Steve Dahl said in a 2004 interview with Keith Olbermann that disco was a fad "probably on its way out. But I think it hastened its demise".[11]

Nile Rodgers, producer and guitarist for the popular disco-era group Chic said "It felt to us like Nazi book-burning. This is America, the home of jazz and rock and people were now afraid even to say the word 'disco'."[3]

According to the book A Change Is Gonna Come, "The Anti-disco movement represented an unholy alliance of funkateers and feminists, progressives and puritans, rockers and reactionaries. The attacks on disco gave respectable voice to the ugliest kinds of unacknowledged racism, sexism and homophobia."[12] Dahl, however, rejected the notion that this was his motivation. "The worst thing is people calling Disco Demolition homophobic or racist. It just wasn't...We weren't thinking like that."[6]

White Sox TV announcers Harry Caray and Jimmy Piersall, who were broadcasting the game for WSNS-TV, commented freely on the "strange people" wandering aimlessly in the stands. Mike Veeck recalled that the pregame air was heavy with the scent of marijuana.[7] When the crate on the field was filled with records, staff stopped collecting them from spectators, who soon realized that long-playing (LP) records were shaped like frisbees. Some began to throw their records from the stands during the game, often striking other fans. The fans also threw beer and even firecrackers from the stands.

After the first game (which Detroit won 4-1), Dahl, dressed in army fatigues and helmet, along with Lorelei Shark, WLUP's first "Rock Girl",[8] and bodyguards, emerged and proceeded to center field. The large box containing the collected records was rigged with explosives. Dahl led the crowd in chants of "disco sucks" and a countdown prior to triggering the explosives. When detonated, the explosives tore a hole in the outfield grass surface and a small fire began burning. Dahl, Shark, and the bodyguards hopped into a jeep which circled the warning track before leaving the field through the right-centerfield exit. Thousands of fans immediately rushed the field. Some lit more fires and started small-scale riots. The batting cage was pulled down and wrecked,[9] and the bases were stolen, along with chunks of the field itself. The crowd, once on the field, mostly wandered around aimlessly,[10] though a number of participants burned banners, sat on the grass or ran from security and police.

Veeck and Caray used the public address system to implore the fans to leave the field immediately, but to no avail. The scoreboard simply flashed, "PLEASE RETURN TO YOUR SEATS." Eventually, the field was cleared by the Chicago Police in riot gear. Six people reported minor injuries and thirty-nine were arrested for disorderly conduct.[6] The field was so badly torn up that the umpires decided the second game couldn't be played, though Tigers manager Sparky Anderson let it be known that his players would not take the field in any case due to safety concerns. The next day, American League president Lee MacPhail forfeited the second game to the Tigers, on the grounds that the White Sox had failed to provide acceptable playing conditions. The remaining games in the series were played, but for the rest of the season fielders and managers complained about the poor condition of the field.

For White Sox outfielder Rusty Torres, Disco Demolition Night was actually the third time in his career he had personally seen a forfeit-inducing riot. He had played for the New York Yankees at the last Senators game in Washington in 1971 and the Cleveland Indians at the infamous Ten Cent Beer Night in Cleveland in 1974. The event was deemed newsworthy worldwide.[3]

According to the 1986 book Rock of Ages: The Rolling Stone history of Rock and Roll, "the following year disco had peaked as a commercial blockbuster".[2] Steve Dahl said in a 2004 interview with Keith Olbermann that disco was a fad "probably on its way out. But I think it hastened its demise".[11]

Nile Rodgers, producer and guitarist for the popular disco-era group Chic said "It felt to us like Nazi book-burning. This is America, the home of jazz and rock and people were now afraid even to say the word 'disco'."[3]

According to the book A Change Is Gonna Come, "The Anti-disco movement represented an unholy alliance of funkateers and feminists, progressives and puritans, rockers and reactionaries. The attacks on disco gave respectable voice to the ugliest kinds of unacknowledged racism, sexism and homophobia."[12] Dahl, however, rejected the notion that this was his motivation. "The worst thing is people calling Disco Demolition homophobic or racist. It just wasn't...We weren't thinking like that."[6]

Although Bill Veeck took much of the public heat for the fiasco, it was known among baseball people that his son Mike was the actual front-office "brains" behind it. As a result, Mike was blacklisted from Major League Baseball for a long time after his father retired. As Mike related, "The second that first guy shimmied down the outfield wall, I knew my life was over!"[7]

To this day, the second game of this doubleheader is still the last game forfeited in the American League. The last game to end in this manner in the National League was on August 10, 1995, when a baseball giveaway promotion went awry and resulted in the Los Angeles Dodgers forfeiture.

Much later, on July 12, 2001, Mike Veeck apologized to Harry Wayne Casey, the lead singer for KC and the Sunshine Band, a leading disco act.[13]

To this day, the second game of this doubleheader is still the last game forfeited in the American League. The last game to end in this manner in the National League was on August 10, 1995, when a baseball giveaway promotion went awry and resulted in the Los Angeles Dodgers forfeiture.

Much later, on July 12, 2001, Mike Veeck apologized to Harry Wayne Casey, the lead singer for KC and the Sunshine Band, a leading disco act.[13]

Actor Michael Clarke Duncan, a Chicago native and 21 at the time, attended the event. He was among the first 100 people to run onto the field and he slid into third base. He also had a silver belt buckle stolen during the ensuing riot[14] and stole a bat from the dugout.[15]

No comments:

Post a Comment